I started the off the Importance Of… series to write about some aspects of software development which are sometimes overlooked. In what was going to be my last post, I mentioned in passing roadmaps. In particular, I said that customer-led developments shouldn’t affect or obstruct the roadmap. The rationale behind this is simple – the roadmap defines where you need to take your product; it effectively defines the primary development objectives. Anything detracting from your primary objectives will by definition be an obstacle for your product.

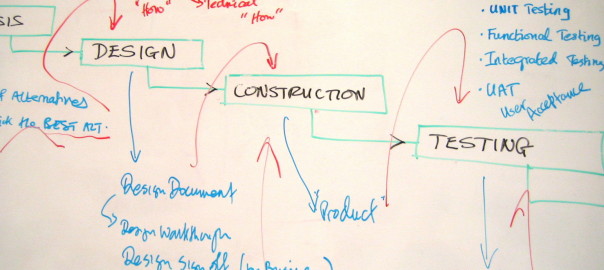

In the first place then, a roadmap will force you to think about the priorities, risks, and rewards of developments planned for your product. In turn, this clarifies the direction of the product – where it’s heading and what it’s aiming to do. And direction is invaluable when it comes to engaging with people, both internally and externally.

Externally, providing a roadmap to customers will boost confidence. It demonstrates that there are objectives, a thought process, a plan. Existing customers know what to expect, can start planning for those deliverables, can see progress as roadmap items are delivered. Potential customers can determine whether it’s the product they’re looking for now or in the future, can see it’s an active project with progressive thinking. A roadmap shows your customers that you are committed to improving your offerings.

Internally, that direction is perhaps even more important. It ensures that everyone is working towards the same goals. Aligned objectives means less friction, and more clarity on what to work on now and next. From a software development perspective, it means it is easier to keep multiple development teams in sync, and easier to plan and schedule work. Dependencies across teams can be identified and taken account of.

For developers in particular, having a roadmap can make architectural decisions a less daunting proposition. People sometimes refer to future-proofing a feature or development. While it is technically impossible to future-proof a software product (the 640K quote, while a misattribution, remains a great cautionary tale), knowing where a product is headed can certainly reduce the number of problems you encounter in the future. It allows developers to consider flexible approaches, discard ones which will not work when other developments come into play, or even delay certain aspects until they can be kept in step. [As an aside, the term future-proof isn’t great for software development, can we use future-harden instead?]

A roadmap is an essential part of any company strategy. Without one, you are lost.

Photo by Scorpions and Centaurs via flickr.